- Homepage

- Bestiary

- Carnivores

- Pachydermata

- Birds of prey

- Bateleur

- Buzzard, Augur

- Buzzard, Common

- Eagle, African Crowned

- Eagle, African Fish

- Eagle, Black-chested Snake

- Eagle, Brown Snake

- Eagle, Long-crested

- Eagle, Martial

- Eagle, Steppe

- Eagle, Tawny

- Eagle, Wahlberg's

- Falcon, Amur

- Falcon, Lanner

- Falcon, Pygmy

- Goshawk, African

- Goshawk, Dark Chanting

- Goshawk, Eastern Chanting

- Goshawk, Gabar

- Harrier, African Marsh

- Harrier, Eurasian Marsh

- Harrier, Montagu's

- Harrier, Pallid

- Hawk, African Harrier

- Hobby, eurasian

- Kestrel, Common

- Kestrel, Grey

- Kestrel, Greater

- Kestrel, Lesser

- Kite, Yellow-billed

- Kite, Black-winged

- Eagle-owl, Verreaux's

- Owl, african scops

- Owl, Marsh

- Secretary Bird

- Sparrowhawk

- Vulture, Egyptian

- Vulture, Hooded

- Vulture, Lappet-faced

- Vulture, Palm-nut

- Vulture, Rüppell's

- Vulture, White-backed

- Vulture, White-headed

- Ongulates

- Antelope, sable

- Bongo

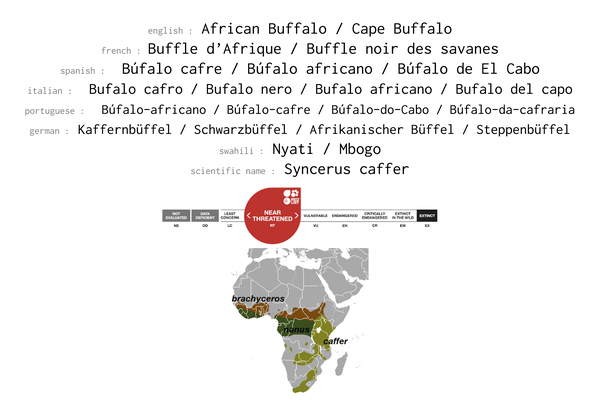

- Buffalo

- Bushbuck

- Bushpig

- Dik-dik, Kirk's

- Dik-dik, Günther's

- Duiker, common

- Duiker, Harvey's

- Eland

- Gazelle, Grant

- Gazelle, Thomson

- Gerenuk

- Giraffe, masai

- Giraffe, reticulated

- Giraffe, Rotschild's

- Hartebeest

- Hog, giant forest

- Impala

- Klipspringer

- Kudu, greater

- Kudu, lesser

- Oribi

- Oryx, east african

- Oryx, fringe-eared

- Reedbuck, Bohor

- Reedbuck, mountain

- Steenbok

- Suni

- Topi

- Warthog

- Waterbuck, common

- Waterbuck, defassa

- Wildebeest

- Zebra, Grevy

- Zebra, hybrid

- Zebra, plain

- Reptiles

- Waders and water birds

- Avocet pied

- Bittern, dwarf

- Coot

- Cormorant, long-tailed

- Cormorant, white-breasted

- Courser, Bronze-winged

- Courser, somali

- Courser, Temminck's

- Courser, three-banded

- Courser, Two Banded

- Crake black

- Crane, grey crowned

- Darter, african

- Duck, african black

- Duck, knob-billed

- Duck, white-backed

- Duck, white-faced whistling

- Duck, yellow-billed

- Egret, cattle

- Egret, great

- Egret, intermediate

- Egret, little

- Flamingo, greater

- Flamingo, lesser

- Goose, egyptian

- Goose, spur-winged

- Grebe, little

- Greenshank, common

- Gull, grey-headed

- Gull, sooty

- Hamerkop

- Heron, black

- Heron, black-headed

- Heron, goliath

- Heron, grey

- Heron, purple

- Heron, rufous-bellied

- Heron, squacco

- Heron, striated

- Night-heron, black-crowned

- Ibis, african sacred

- Ibis, glossy

- Ibis, hadada

- Jacana, African

- Lapwing, Senegal

- Moorhen, common

- Painted-snipe, greater

- Pelican, great white

- Pelican, pink-backed

- Plover, blacksmith

- Plover, black-winged

- Plover, caspian

- Plover, crowned

- Plover, kittlitz's

- Plover, long-toed

- Plover, ringed

- Plover, spur-winged

- Plover, three-banded

- Plover, wattled

- Pratincole, collared

- Ruff

- Sandpiper, common

- Sandpiper, green

- Sandpiper, marsh

- Sandpiper, wood

- Sandplover, greater

- Snipe, common

- Spoonbill

- Stilt

- Stint, little

- Stork, abdim's

- Stork, african openbill

- Stork, black

- Stork, marabou

- Stork, saddle-billed

- Stork, white

- Stork, woolly-necked

- Stork, yellow-billed

- Teal, common

- Teal, Hottentot

- Teal, red-billed

- Teal cape

- Tern, white-winged

- Tern, whiskered

- Thick-knee, spotted

- Thick-knee, water

- Terrestrial birds

- Bustard, black-bellied

- Bustard, buff-crested

- Bustard, Hartlaub's

- Bustard, kori

- Bustard, white-bellied

- Francoli, coqui

- Francolin, crested

- Francolin, Hildebrandt's

- Francolin, Jackson's

- Francolin, red-winged

- Francolin, Shelley's

- Guineafowl, helmeted

- Guineafow, vulturine

- Hornbill, southern ground

- Ostrich, masai

- Ostrich, somali

- Sandgrouse, black-faced

- Sandgrouse, chesnut-bellied

- Sandgrouse, yellow-throated

- Spurfowl, red-necked

- Spurfowl, yellow-necked

- Birds

- Apalis, yellow-breasted

- Babbler, arrow-marked

- Babbler, brown

- Babbler, northern pied

- Barbet, d'Arnaud's

- Barbet, red-and-yellow

- Barbet, red-fronted

- Batis chin-spot

- Bee-eater, blue-cheeked

- Bee-eater, little

- Bee-eater, cinnamon-chested

- Bee-eater, eurasian

- Bee-eater, olive

- Bee-eater, somali

- Bee-eater, white-throated

- Bee-eater, white-fronted

- Bishop, yellow

- Bishop, Zanzibar red

- Bishop, yellow-crowned

- Boubou, tropical

- Boubou, slate-coloured

- Bulbul

- Bush-shrike, sulphur-breasted

- Bunting, cinnamon-breasted rock

- Bush-shrike, rosy-patched

- Camaroptera, grey-backed

- Canary, brimstone

- Canary, yellow-crowned

- Chat, alpine

- Chat, anteater

- Chat, cliff

- Chat, sooty

- Chatterer

- Cisticola, Aberdare

- Cisticola, desert

- Cisticola, Hunter's

- Cisticola Lyne's

- Cisticola, rattling

- Cisticola, stout

- Cisticola, winding

- Citril, african

- Cordon-bleu

- Coucal, white-browed

- Coucal, black

- Crow, house

- Crow, pied

- Cuckoo, african

- Cuckoo, african emerald

- Cuckoo, common

- Cuckoo, Diederik

- Cuckoo, great spotted

- Cuckoo, red-chested

- Dove, african mourning

- Dove, dusky turtle

- Dove, emerald-spotted wood

- Dove, namaqua

- Dove, laughing

- Dove, red-eyed

- Dove, ring-necked

- Drongo, fork-tailed

- Firefinch

- Fiscal, northern

- Fiscal, grey-backed

- Fiscal, long-tailed

- Fiscal, Taita

- Flycatcher, african dusky

- Flycatcher, african grey

- Flycatcher, african paradise

- Flycatcher, spotted

- Flycatcher, southern black

- Flycatcher, white-eyed slaty

- Go-away-bird

- Grenadier, purple

- Hoopoe

- Hoopoe, green wood

- Hornbill, african grey

- Hornbill, Jackson's

- Hornbill, Von Der Decken's

- Hornbill, red-billed

- Hornbill, eastern yellow-billed

- Hornbill, sylvery-cheeked

- Hornbill, crowned

- Indigobird, village

- Kingfisher, grey-headed

- Kingfisher, giant

- Kingfisher, malachite

- Kingfisher, pied

- Kingfisher, striped

- Kingfisher, woodland

- Lark, pink-breasted

- Lark, red-capped

- Lark, rufous-naped

- Longclaw, pangani

- Longclaw, rosy-breasted

- Longclaw, yellow-throated

- Lovebird

- Mannikin, bronze

- Mannikin, rufous-backed

- Mousebird, blue-naped

- Mousebird, speckled

- Mousebird, white-headed

- Oriole, black-headed

- Oriole, african golden

- Oxpecker, yellow-billed

- Oxpecker, red-billed

- Parrot, brown

- Parrot, red-bellied

- Pigeon, african green

- Pigeon, speckled

- Pipit, grassland

- Pipit, plain-backed

- Pipit, golden

- Quail-finch

- Quelea red-billed

- Raven, white-necked

- Raven, fan-tailed

- Robin-chat, Cape

- Robin-chat, white-browed

- Roller, eurasian

- Roller, lilac-breasted

- Roller, purple

- Rook, Cape

- Scimitarbill

- Scimitarbill, Abyssinian

- Scrub Robin, white-browed

- Seedeater, streaky

- Seedeater, yellow-rumped

- Shrike, lesser grey

- Shrike, red-backed

- Shrike, northern white-crowned

- Shrike, Isabelline

- Silverbird

- Sparrow, chesnut

- Sparrow, grey-headed

- Sparrow, rufous

- Sparrow, yellow-spotted bush

- Sparrow-Lark Fischer's

- Sparrow-weaver, Donaldson-Smith's

- Sparrow weaver, white-browded

- Starling, black-bellied

- Starling, bristle-crowned

- Starling, Fischer's

- Starling, Golden-breasted

- Starling, greater blue-eared

- Starling Hildebrandt's

- Starling, red-winged

- Starling, Rüppell's

- Starling, slender-billed

- Starling, superb

- Starling, violet-backed

- Starling, wattled

- Sunbird, amethyst

- Sunbird, beautiful

- Sunbird, bronze

- Sunbird, eastern double-collared

- Sunbird, golden-winged

- Sunbird, Hunter's

- Sunbird, malachite

- Sunbird, mariqua

- Sunbird, eastern violet-backed

- Sunbird, purple-banded

- Sunbird, scarlet-chested

- Sunbird, scarlet-tufted malachite

- Sunbird, tacazze

- Sunbird, variable

- Swallow, barn

- Swallow, red-rumped

- Swallow, lesser striped

- Swallow, wire-tailed

- Tchagra, black-crowned

- Tchagra, brown-crowned

- Thrush, abyssinian

- Thrush, common rock

- Thrush, spotted morning

- Tit, red-throated

- Tit, white-bellied

- Wagtail, african pied

- Wagtail, western yellow

- Warbler, grey-capped

- Warbler, moustached grass

- Warbler, willow

- Waxbill, common

- Weaver, african golden

- Weaver, Baglafecht

- Weaver, black-capped social

- Weaver, chesnut

- Weaver, grey-capped social

- Weaver, grosbeak

- Weaver, Holub's golden

- Weaver, northern masked

- Weaver, parasitic

- Weaver, red-billed

- Weaver, red-headed

- Weaver, spectacled

- Weaver, speckle-fronted

- Weaver, Speke's

- Weaver, Taveta golden

- Weaver, village

- Weaver, vitelline masked

- Weaver, white-headed buffalo

- Wheatear, abyssinian black

- Wheatear, capped

- Wheatear, isabelline

- Wheatear, northern

- Whinchat

- Whydah, paradise

- Whydah, pin-tailed

- Widowbird, Jackson's

- Widowbird, red-cowled

- Widowbird, white-winged

- Widowbird, yellow-mantled

- Woodpecker, grey

- Wodpecker, nubian

- Wren-Warbler , Grey

- Primates, Rodents and Others

- Baboon, olive

- Baboon, yellow

- Colobus, angolan

- Colobus, guereza

- Galago, greater

- Hare

- Hyrax, rock

- Hyrax, bush

- Mongoose, banded

- Mongoose, dwarf

- Mongoose, slender

- Mongoose, white-tailed

- Mole rat, naked

- Monkey, blue

- Monkey, patas

- Monkey, vervet

- Porcupine

- Rat, afroalpine vlei

- Squirrel, unstripped ground

- Squirrel, ochre bush

- Squirrel, red bush

- Chiromantis petersii

- B&W Gallery

- Buy prints

- Contact

Carnivores Pachydermata Ongulates Reptiles Primates, rodents and others Birds Birds of prey Terrestrial birds Waders and water birds

Cape Buffalo

Cape buffalo, (Syncerus caffer caffer), also called African buffalo, the largest and most formidable of Africa’s wild bovids (family Bovidae). The Cape buffalo is not very tall—it stands only 130–150 cm tall and has relatively short legs—but it is massive, weighing 425–870 kg. Bulls are about 100 kg heavier than cows, and their horns are thicker and usually wider, up to 100 cm across, with a broad shield (only fully developed at seven years) covering the forehead. The coat is thin and black, except in young calves, whose coats may be either black or brown.

One of the most successful of Africa’s wild ruminants, the Cape buffalo thrives in virtually all types of grassland habitat in sub-Saharan Africa, from dry savanna to swamp and from lowland floodplains to montane mixed forest and glades, as long as it is within commuting distance of water (up to 20 km). It is immune to some diseases that afflict domestic cattle in Africa—in particular, the bovine sleeping sickness (nagana) transmitted by tsetse flies.

To sustain its bulk, the Cape buffalo must eat a lot of grass, and therefore it depends more on quantity than quality. It is able to digest taller and coarser grass than most other ruminants, has a wide muzzle and a row of incisor teeth that enable it to take big bites, and can use the tongue to bundle grass before cropping it—all bovine traits. When grass is scarce or of too poor quality, buffaloes will browse woody vegetation. The largest populations occur in well-watered savannas, notably on floodplains bordering major rivers and lakes, where herds of over 1,000 are not uncommon.

Extremely gregarious, buffaloes are one of the few African ruminants that lie touching. Herds include both sexes and live in traditional, exclusive home ranges. Clans of related females and offspring associate in subgroups. A male dominance hierarchy determines which bulls breed. All-male herds are predominately old and sedentary, as are lone bulls. Calves are born year-round, after a nine-month gestation. Though weeks pass before calves can keep up with a fleeing herd, they do not go through a hiding stage but follow under their mothers’ protection as soon as they can stand. Herds also cooperatively defend members; they put to flight and even kill lions when aroused by distress calls.

Source : Britannica.com